Poly-Luna was the design practice by Luna Maurer from 2001-2012. In 2012 she co-founded Moniker with Roel Wouters and Jonathan Puckey who left in 2016. In 2023 Moniker closed its doors.

Luna Maurer was also part of the Conditonal Design Collective with its manifesto and platform conditionaldesign.org.

This site is an archive and won't be updated with projects. Recent works can be found under lunamaurer.com

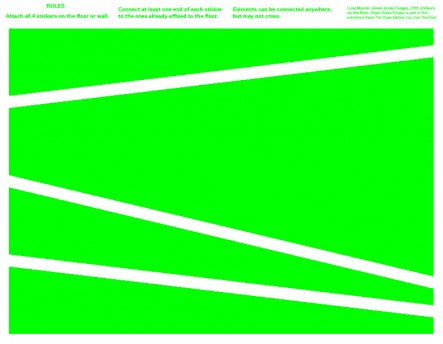

Green Grass Fungus, 2011

1 / 8

Green Grass Fungus is a new variation of the 'Fungus-Series'. It was

executed as part of the exhibition 'Read The Rules Before You Use The Pool', Index Festival, New York, 18th - 27th of august 2011.

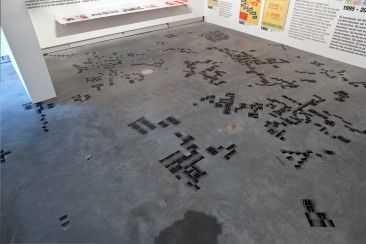

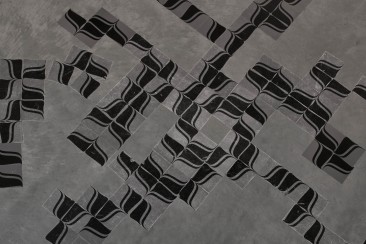

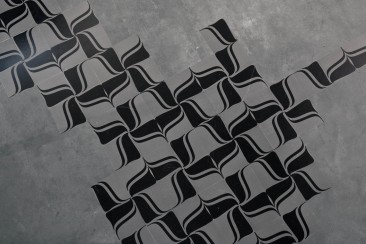

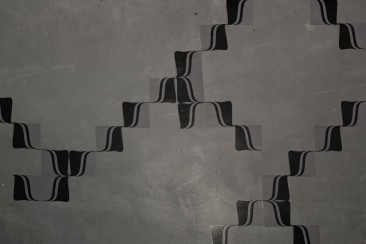

Kaba Fungus, 2011

1 / 11

Kaba Fungus was spreading on the floor during the exhibition 'Connecting the Past and the Future

- Graphic Design Collection in the 21st century' Graphic Design

Museum Breda from January till May. Kaba Fungus is based on the

'Kaba-ornament' (1985) by Bram de Does.

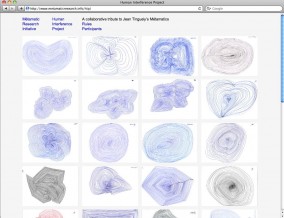

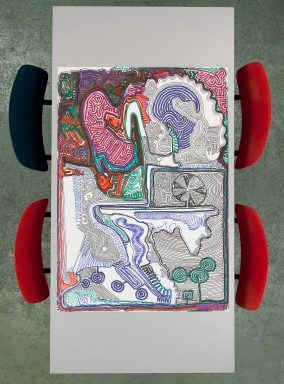

Human Interference Project, 2011

1 / 3

The

Human Interference Project

is part of the Metamatic Research Initiative. We create a big

collection of hand drawn mathematical figures. The drawings are a

tribute to the M�tamatics, the drawing machines by Jean

Tinguely.

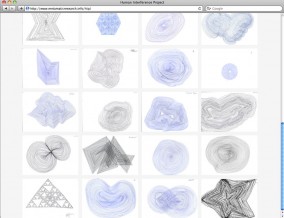

Metamatic Research Initiative website, 2011

The website serves not only for documenting the project of the

Metamatic Research Initiative but is a platform where everyone

interested in the topic of Jean Tinguely's work can participate. As

part of the design a group of artists, designers, friends and fans

of the MRI project were invited to make closely guided

line-drawings, according to a set of rules.

www.metamaticresearch.info

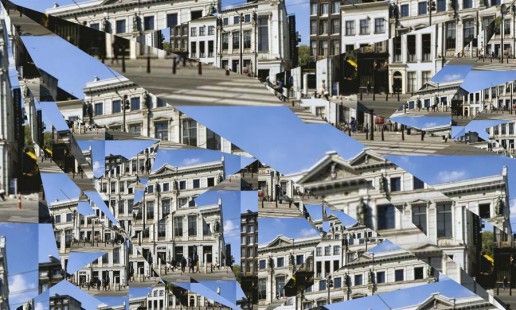

Flyer tool for Arti et Amicitiae, 2011

This application is the new flyer of the exhibitions in

Arti et Amicitiae, a gallery space

in Amsterdam. The collectively modified images get printed and

distributed. In collaboration with

Jochem van der Spek.

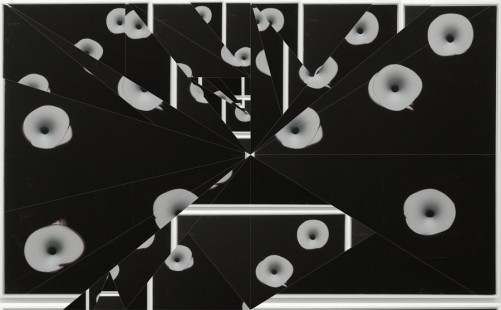

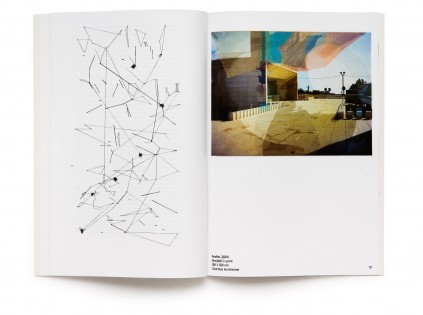

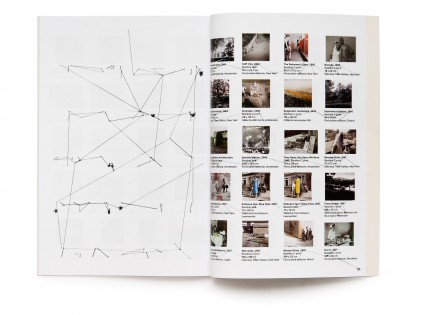

Berend Strik, 2010

1 / 7

Catalogue and website for artist Berend Strik. The catalogue uses

the sewing atelier of Berend Strik a s tool for the typography.

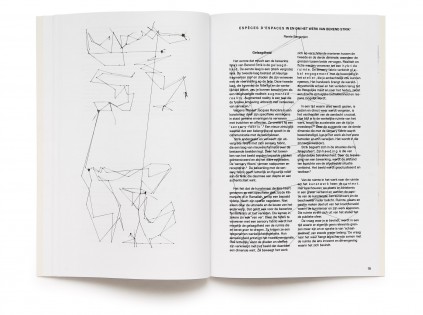

Playful users and intelligent systems, 2010

A dialogue between Luna Maurer and Andreas Zangger on the

interaction of humans and machines, on designing systems, and on

participation of the users.

A commissioned text for Caroline Nevejan and the knowledge database on 'Witnessed Presence'. This dialogue tries to investigate the questions that arise in the context of our practice. Luna Maurer is a designer and artist working in the field of digital media. Andreas Zangger is historian of science and of transnational networks. The work of Luna Maurer serves as a bracket for our dialogue. But there will be references to other thinkers, artists and people. Some of the mentioned projects of Luna Maurer are presented separately. The three dialogues each have a general topic: the first deals with the relationship of humans and machines, the second on designing system and the idea of constraints and freedom in the process, and the third about users and the intelligence of the crowd.

A commissioned text for Caroline Nevejan and the knowledge database on 'Witnessed Presence'. This dialogue tries to investigate the questions that arise in the context of our practice. Luna Maurer is a designer and artist working in the field of digital media. Andreas Zangger is historian of science and of transnational networks. The work of Luna Maurer serves as a bracket for our dialogue. But there will be references to other thinkers, artists and people. Some of the mentioned projects of Luna Maurer are presented separately. The three dialogues each have a general topic: the first deals with the relationship of humans and machines, the second on designing system and the idea of constraints and freedom in the process, and the third about users and the intelligence of the crowd.

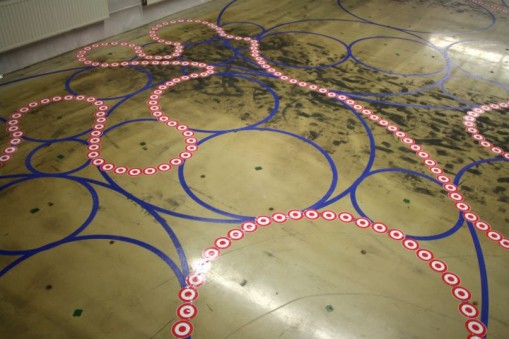

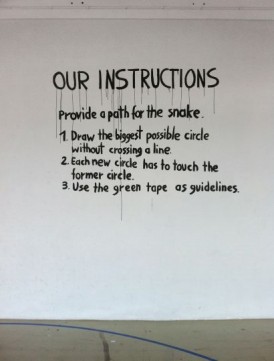

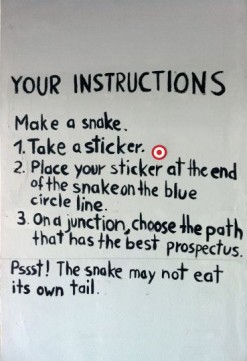

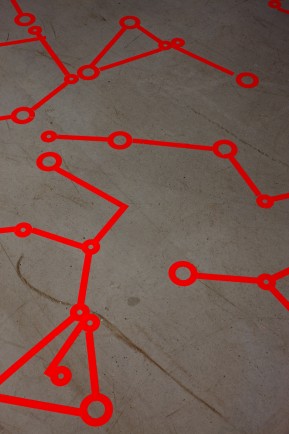

Tape on Floor 4, 2010

Collaborative installtion at

Flux/S in Eindhoven, NL with

Conditional Design, 9-12 Sept 2010. The 1200 m� on the 4th floor of

the SBP-building acted as the surface of our playing field. The

Court-Line� Tape Machine served as our pen. Visitors received round

stickers. Together with the visitors we generated the circular

pattern on the floor during the four days of the festival. We and

the visitors were bound to certain rules.

STEIM Crackle Type Tool, 2010

1 / 11

STEIM Windows, 2010

1 / 7

4 different window designs for

STEIM, Amsterdam. The letters

STEIM are the base for the 4 different patterns on each window.

Glued with 3M Scotch Magic Removable tape.

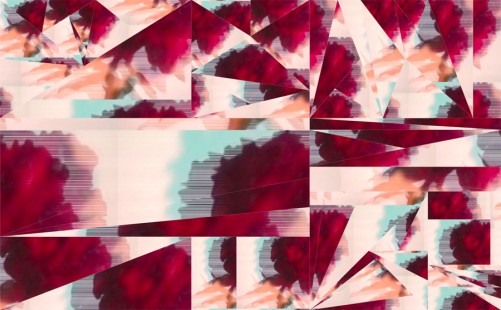

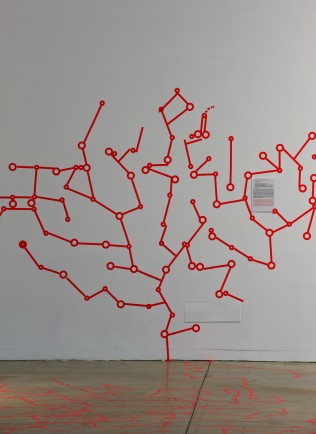

Red Fungus, 2010

1 / 10

After 2 months

Part of the exhibition

Process as Paradigm, 23.04 - 30.08.2010 at LABoral, center for arts and science,

Gijon, Spain.

Red Fungus is a follow up to Blue Fungus, but with different rules. Visitors to the exhibition are given a sheet of four stickers upon entering the museum. They are then asked to affix these stickers on the exhibition floor, according to a simple set of rules.

Red Fungus is a follow up to Blue Fungus, but with different rules. Visitors to the exhibition are given a sheet of four stickers upon entering the museum. They are then asked to affix these stickers on the exhibition floor, according to a simple set of rules.

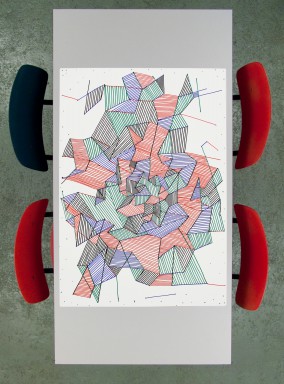

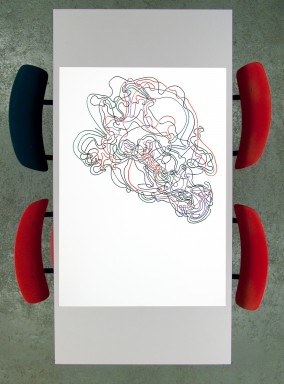

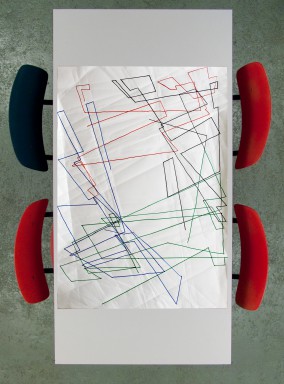

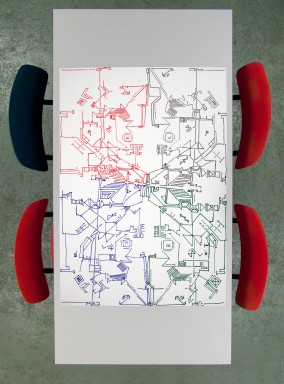

Conditional Design Posters, 2009

1 / 7

A selection of posters from the 'Conditional Design Tuesdays', the

meetings at Luna's kitchen table.

Paper size: 70 x 100 cm

4 different colors pen: red (Jonathan), green (Roel), blue (Luna), black (Edo).

Edition: 1

Paper size: 70 x 100 cm

4 different colors pen: red (Jonathan), green (Roel), blue (Luna), black (Edo).

Edition: 1